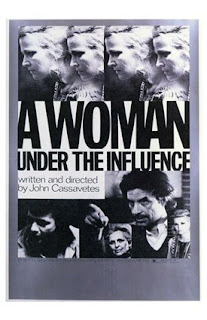

Written & Directed by: John Cassavetes

Starring: Gena Rowlands, Peter Falk

Color, 155 minutes

Grade: A+

John Cassavetes. Anyone who loves cinema, whether they've seen his films or not, knows the name. His reputation has established him, quite rightly, as the father of independent cinema in America. As an actor he was notorious for hating directors and taking roles simply for the money. As a writer/director, he is famous for the way that he pushed actors, audiences, and himself to new heights. While watching one of his films you become immediately aware that you have never seen anything quite like it, and that you are in the hands of a man who lived and breathed cinema. Personally, I've always considered myself a modest fan of his work; I liked

Shadows, I saw the talent and unique spirit in

Faces even though I felt the film was more than a bit dated, and I was won over by the low key, character driven narrative in

The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. Now I've just seen 1974's

A Woman Under the Influence, and it's finally become apparent to me just how much of a genius this man was, for it is this film that encapsulates everything that Cassavetes stood for as a filmmaker. One of the greatest films of the 1970's,

A Woman Under the Influence is a masterpiece of personal filmmaking.

The story focuses on Nick and Mabel Longhetti, played by Peter Falk and Gena Rowlands (Cassavetes' wife and most frequent collaborator), a married couple living in Los Angeles. Nick is a construction supervisor; Mabel stays at home to care for their three children. As the film opens, we see Nick and his coworkers leaving work. They stop to get a quick beer before heading home, but while sitting there, a phone call comes through telling them they have to work a double shift. Nick gets on the telephone and begins shouting. "I have an unbreakable date," he says forcefully, "with my wife." Nick continues to shout over the receiver for a few more minutes before hanging up. His coworkers applaud his performance and thank him for telling off the boss. They all finish their drinks, and get back on the road to start another long shift. At home, Mabel is unaware that Nick will be late coming home. She's getting the children ready for a stay with their grandmother (Lady Rowlands, Gena's mother). The children rush out the door, piling, one by one, into grandma's car. Mabel, frantically hopping around on one foot, packs the kids' things into the trunk, yelling at everyone to hurry up and be careful. Once everything is ready to go, Mabel lectures and scolds her mother for a good three minutes about keeping the kids safe. "I don't want you to be chickenshit and not calling me," Mabel shouts at her mother. That's normally not a very effective way to get a message across to someone who carried you in her womb for nine months, but grandma quietly nods in agreement. Mabel kisses the kids and waves them off, then rushes back into the house to prepare for an evening with her husband. Nick, however, is nervous about calling Mabel, afraid of what she'll do when she hears the bad news. A coworker comforts Nick, but then makes the mistake of calling Mabel crazy. "Mabel's not crazy," Nick says unconvincingly, "she's unusual." Taking a few moments to muster up the courage, Nick proceeds with the phone call. To his surprise, Mabel isn't upset, she doesn't scream, she doesn't argue, she just tells Nick that everything is alright. The phone conversation ends, Nick goes to work, and Mabel heads out for a night on the town.

In a bar, Mabel meets a man named Garson Cross (affectionately played by O.G. Dunn). He buys her a drink, and the two go back to her place. She's visibly drunk and she begins to fight him off, but Cassavetes effectively cuts quickly to the next morning, with Mabel lying in bed, and Cross wandering around the house. "Nick," she screams while rushing into the bathroom, slamming the door behind her. Cross, bewildered, follows her and yells at her through the door. She rushes out of the bathroom and speaks to Cross as if nothing unusual has taken place, in fact, she refers to him as Nick. The real Nick, however, is on his way home, and he's brought along his coworkers for a late dinner/early breakfast. The workers pile through the door of the Longhetti house, and the audience notices that there is no sign of Garson Cross. Did he leave on his own? Did Mabel kick him out? Does this sort of thing happen quite often? Is Mabel even aware of it? Cassavetes keeps us in the dark, he doesn't spoon feed us. He keeps the attention on Mabel's interaction with Nick's coworkers. She introduces herself to them, slowly shaking each hand. She knows some of these men, she remembers them. Others tell her that they've met in the past, one even says he had dinner there only two weeks ago. "I remember your wife," Mabel says, "but I don't remember you." Nick's coworkers know that Mabel is a little kooky and they try to be respectful, but it becomes increasingly difficult for them not to laugh. Nick does his best to take it in stride, but at times he blows his top. During the meal, Mabel begins to ask some of the men if they want to dance. Each man refuses while throwing a glance at Nick. Mabel does her best to persuade them, to no avail. She gets in their faces, even complimenting one of the men on his handsome face. Nick, finally having enough, shouts at her. "Get your ass down," he screams at her, and the table begins to clear out. The men say thank you to both Mabel and Nick, and then leave.

This spaghetti scene takes place very early, but it is essential to the film's success. The scene is a microcosm of this couple's entire relationship. Mabel is a friendly person who tries to be nice and welcoming of everyone, but she becomes too much to handle. Calling her crazy wouldn't be accurate, she's just too frenetic, she gets lost in her own head. She says weird things, but she doesn't mean any harm. She mumbles to herself, but it's almost as if too many thoughts are running through her mind at one time and when she reaches out to latch onto to one of them, she finds it impossible to process. Nick obviously loves her, and understands her. Cassavetes proves this to us by cutting back and forth from her exasperated expressions to his reassuring nods and winks. Unfortunately, Nick, like anyone, has his breaking point, and when breached, he explodes. He tolerates as much as he can, but he's always beat out by his own temper. In this one, seemingly simple scene, Cassavetes manages to give us the entire history of this relationship.

After the spaghetti breakfast, the film pushes on rather quickly. Nick takes his mother (Katherine Cassavetes, John's mom) to the doctor, Mabel waits for her children at the bus stop, shouting at people to tell her the time of day. She brings the children home, and has a party for them, inviting a few local kids to come and play. Mr. Jensen (Mario Gallo) brings the kids over, and after witnessing Mabel's unusual personality, decides to take his children home. Unfortunately for him, Mabel has sent the children to find some costumes and play dress up. Jensen is in the process of getting his children dressed when Nick returns, his mother in tow. Nick, seeing his daughter running around naked, becomes angry and rushes upstairs to find Mabel. She's there, of course, but so is Mr. Jensesn, struggling with his children. Nick blows his lid, slaps Mabel, and gets into a fight with Jensen. With Jensen and his children gone, Nick nurses his bloody lip, and calls the doctor to come over and try to figure out what's going on with Mabel. She's uncannily calm, though, acting normal, and then the doctor shows up, sending her into a fit. Nick tries to keep her calm, but his mother throws fuel onto the fire. Yelling at the doctor to give Mabel a shot, Nick's mother is certainly not helping matters. Nick does his best, but he gives in to his mother, and after Mabel finally has her meltdown, disintegrating into tears, the doctor gives her an injection and informs her that she will be committed to an institution.

This first half is so incredibly wrenching that we wonder if there is any hope in this story at all. Cassavetes will never give us an easy way out, but he's not a pessimist. We see Nick struggle to be a good father, but he seems to forget that his children are still children. At the beach, he shouts at them, almost forcing them to play and have a good time. In the bed of a truck, he opens a six-pack and lets the children pass a can around. The audience gets the feeling that maybe it's Nick that should have been committed, not Mabel. She may have had a few screws loose, but she never put anyone in danger, she never hurt a soul. Eventually, six months later, Mabel does return home, noticeably changed by her treatment. She tells stories of shock therapy, but her family refuses to listen. She's home, that's all that matters. Nick, however, is not content. He wants the old Mabel. He wants the way she used to sputter at people, the way she would flick her thumb. He wants to listen to her broken, unintelligible sentences; he wants to see her hop around energetically, yelling at everyone to "have fun." He misses these things, and he realizes he was wrong to send her away. He loved her the way she was, warts and all, and after a heartbreaking climax, Cassavetes finds a way to leave his audience on a high note. In a film full of shouting, Cassavetes leads his characters, and audience, to a quiet, reflective place that puts everything into perspective.

Cassavetes' films always featured a high caliber of acting, and this one is no exception. Rowland's, even today, is unable to give a bad performance, but her work here is a landmark. Cassavetes gives her the role of a lifetime, and she nails it. She's a force of nature, and Mabel's breakdown is one of the most compelling scenes that I've ever witnessed. But with all the heaps of praise that have been thrown at Rowlands for her performance, Falk often gets the short end of the stick. Always a consummate professional, Falk has a special way of keeping audiences glued to their seats. Whether he was playing Columbo, doing great character work like he does here, or even playing an angelic version of himself in Wim Wenders' masterful

Wings of Desire, Falk is always at the top of his game. In many ways, he has the harder role here. It's easy for audiences to hate his character, and he knows this, so he makes sure we see the understanding in his face, the love in his eyes. Nick is an asshole, sure, but he's not a horrible person. Because of his anger, the film is often seen as a kind of feminist parable, but it is inaccurate to try to peg it as such. Pretend that the title of the film is

A Man Under Pressure, and the film takes on an entirely different meaning.

The fact is that Nick and Mabel are right for each other. As individuals, they are impossible, but together, they complete each other. Each one makes up for the others flaws, and they are able to function. They love their children, and they love each other. It may not be a perfect situation, but somehow it works. In Nick's care, the children get drunk, but when Mabel is around, the parents work as a unit, and they are able to keep each other in check. It doesn't take a genius to raise a child, nor does it necessarily take what we consider to be "sane" individuals, it takes love and understanding. Once you have that, the rest, no matter how unlikely, seems to fall into place. Cassavetes knew this and one wonders how much of this material comes from his own life. It's not out of convenience that he cast his mother and mother-in-law, it's not an accident that Nick and Mabel have three children (Cassavetes and Rowland did also). Cassavetes, contrary to popular belief, was not that improvisational, his words, his characters, and his actions were all very deliberate. Maybe he was a man under the influence of the powers of cinema, and maybe it took Rowlands to understand him. They had a love that was as unbreakable as Nick and Mabel's, and it boiled over into their work. This is their crowning achievement.